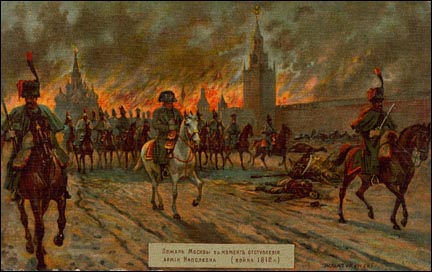

Fig. 1. Retreating Napoleon's Army burns Moscow.

From the 19th century painting

Russian Archival Research: Challenges and Strategies for Success

The following is the edited transcript of the presentation at the 23rd International Conference on Jewish Genealogy, Washington DC, July 24, 2003.

It is presented in a draft form; footnotes and hyperlinks will be added shortly...

The title of this talk is a bit misleading because what we call Russia - in the genealogical sense - really applies to the vast territory from the Polish-German border all the way to Japan. In fact, I will discuss at some length analyzing records created in Russian Poland. As you may know I am mostly interested in the difficult challenges of research, when we cannot find an ancestor, or a living

relative; in other words I am drawn by brick walls, dead ends, and black holes. When we are careful and observant, we can often take cues

in our research and be helped by such unlikely personalities as Zorro and Alexander Dumas, let alone such an authority on all kinds of

searches as the Central Intelligence Agency.

When I started working on this talk a few months ago, I re-read my presentation at the LA Conference in1998 and would like to share with you the topics covered back then because they provide an important frame of reference on today’s subject:

- Uniqueness of Jewish genealogical research

- 2 principles:

1. we already have what we seek

2. Comprehensive Approach - There is no substitute

- Verifying Genealogical Evidence

- primary vs. secondary sources

- date estimates

- family name change; family name study

- types of documents

- ship manifest problems

- Vsia Rossiia

- There is no substitute for knowledge

- misconceptions

- cross-cultural misconceptions

- geography problems

- residence outside the Pale of Settlement

- Finding living relatives

- Reach out to former Soviet Jews

Many of the topics are still important, still persistent, and still need to be addressed, in part because of the constant influx of new people into the field of genealogy. It is exciting, because

new people means finding new relations and new friends, and learn new ideas.

To me, the most important topic from 1998 is: There is no substitute for

knowledge. To which I might add - and for patience; and for coolness and for clarity of mind; and for being methodical and systematic. These qualities are always helpful, especially when we expand research into a foreign country, where problems are compounded by strange languages, equally strange history, and still stranger working habits of local archivists.

Unanswerable questions

So, what could be - pardon the expression - a road map to success? When we embark on research we usually have a lot of questions and the first topic I’d like to cover is what questions not to ask, yourself or others, because

some questions are unanswerable.

There is a truism that a properly formulated question contains half the answer. Analysis of inquiries I receive, and those we can see on the internet indicates that in many cases genealogists have not thought through their questions and may not even have a clear research goal.

Some of these questions cry in the subject line:

Subject: Re: Help! Lost immigrant!

Subject: Dilemma - names I'm searching keep changing!

Subject: How do I trace a seemingly totally untraceable New

York family?!

Subject: Can this lead be followed?

More recent examples:

• Do you know of Nathan GOLDMAN, born in Russia, approx. in the 1850's to 1860's?

• Could someone please explain the usage of the term

Patrynomic...

• Has anyone actually found the name of the

shletl on these manifests as opposed to just the words "Russia" or "Poland"... I wonder if this is worth my while--searching all these manifests.

It is so easy to be sarcastic and tell somebody No, do not follow this lead, it is not worth your while. Better take your spouse to a Chinese restaurant, it’s cheap, filling, and less aggravating. But the questions do remain, they are legitimate. They just need to formulated in a better way which will likely elicit a meaningful reply.

It is a good idea to develop a system - whichever is comfortable for you - to quickly locate and analyze the information that may help you to find a missing person. We do not start in a vacuum, we always have some initial data, e.g. name, location, time period. So, to succeed in your search, you must become an expert on that name, that location, and that time period. If you are tenacious and lucky, you will come across that piece of a puzzle with a familiar shape.

For the sake of this discussion, let us suppose that your great-grandfather Morris Goldman came to the States in 1903 from the

shletl of Smorgon in the Vilna Guberna. You even found him in a the ship manifest where you also discovered there was another entry, for Nosel Goldman, from the same shletl. This is the first time ever you see this name. There is no Nosel in your family. What do you do? There are two things you can do. First, you rush to your computer and cry

“Help! Lost immigrant!”. What will be the outcome? A lot of I feel your pain emails.

Alternatively, you take a deep breath and start thinking. What will be the outcome of this thinking process? Very possibly, a headache. But it will go away - I promise - and your mind will clear as soon as you start asking yourself simple common sense questions, such as:

What facts can you derive from the ship manifest?

* Fact one. Two people were registered in the ship manifest.

* Fact two. A man named Moishe Goldman in the ship manifest came to the US. He became Morris and you are his great-grandson.

That’s the end of the facts. The rest are conjectures:

1. Nosel Goldman never came to the US. Why? Maybe he died during the voyage, or was sent back. Did you check the entire manifest, including the attachments and notes?

2. Nosel Goldman was not called Nosel or Nathan Goldman in the US. He was the enlightened younger brother of your great-grandfather, called originally Nosel-Lejb and known in your family as Leonard.

3. Nosel Goldman was not called Nosel Goldman either in the US, or in Russia. He was a landsman, most likely from Smorgon, who had to be brought to America. Somehow he obtained documents for Nosel Goldman and posed as Morris’ brother. Where can you go with this idea? You can broadcast it to the world, but the question now becomes more specific:

Do you have an ancestor from Smorgon or the area who came to the US in 1903 as Nosel or Nathan Goldman which was not his real name.

4. Nosel Goldman was his real name, he did come to the US, you found some other information to prove it, but he vanished after 1904 and that’s why you have not heard his name before. What has happened? Many things could have happened. He died, he moved to

Connecticut to sell dry goods, he developed TB and was sent to Denver, he went back to Russia, he intermarried a Galitzianer from Chernowitz and moved to Baltimore. It sounds like nonsense, because it is coming from me now, but in your case, you may have been sitting for a long time on some orphan information about a Falikman family who

once lived in Baltimore and then a woman from that family married a college professor and moved to California, and they are somehow related but nobody knows how. Now it is time to check.

You may come up with even more suppositions because each case is based on the information that you

already possess. That is why, as I was thinking of these hypothetical situations, it reminded me of a brilliant five year old idea of mine: we already have what we seek, but in our quest for new information we often forget to revisit our accumulation of the past 10-20 years of work.

Throwing the net

The second most common version of this problem is when we do not know where in “Russia” our ancestors lived. Or, as one genealogist put it “Has anyone actually found the name of the shletl on these manifests as opposed to ... "Russia" or "Poland”.

So, how do we begin the process if we are fairly certain that our ancestors came from "Russia" or "Poland". First, we must collect as much information on our American family as possible, and know intuitively what given name pattern is likely to be “ours”, including Hebrew

names. We must also memorize as many faces from the family pictures as we can.

And we must know - beforehand - all possible spelling variations of the last name, and how it was written in other languages, e.g. Russian or Polish, in both printed and written forms.

The next step is to throw the net literally all over the world. We may be deluged by the amount of information found, but we do not have to analyze it all right away. At this stage in the research our intuitive knowledge of the naming pattern and faces will serve as our guide. If we do find a promising candidate, we then start a more serious analysis.

What do I mean by “throwing the net all over the world”? The obvious answer is

well, you search the internet. But before we begin the search, it is useful to remind yourself of the three caveats:

- the entire body of knowledge has not been computerized yet,

- what is computerized, is filled with errors, and

- if it’s on the web today, it may be gone tomorrow.

The following is the short list of the sources, mostly web-based.

1. Web search engines. The results will include both historical and contemporary information. I do it 3-4 times a year.

I use Google, which has become the most

popular engine. There are search engines that draw results from more then one

other engines. Find what you like and follow it.

2. Genealogical databases (web and print). There is the Ellis

Island database, there is the Family Tree of the Jewish People,

which we discus later, there is the Social Security Death Index, best accessible

from the fantastic web site of Stephen

Morse, and many others. There is number of databases and name

compilation from the pre-Internet era, that are available in print form only.

3. Library catalogues, especially the Library of

Congress. Consider it a compilation of names, which can be found not only in the Author field, but also in the Subject field.

4. Business directories and phone books. a) historical; b) modern. Web-based directories is a recent phenomenon, and they cannot be searched with the help of the soundex code. That is why it’s useful to browse the white pages whenever you can. You may come across a Veldbloem name

for example in the Amsterdam directory, which is phonetic twin of the Feldblum surname.

Telephone directories from Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania, and other former Soviet republics are available on the web as well. Some of them, e.g.

Moscow and St. Petersburg directories allow Latin character input. Unfortunately, many of them change servers all too often,

so if you come across a directory for the city of your interest, do spend time and make searches for all names that you can think of. A month or a year later the directory may not be there any longer.

5. Alexander Beider’s Reference books, which are an excellent starting point in research.

Detail discussion of these searches can easily expand into a separate presentation. I will only note here that in the case of historical information, the next step would be its analysis, while in the case you found contemporary information, e.g. a Feldblyum who published an article, you may contact this person. Of course, they often do not know much of their own history, unless they are as interested in it as you are interested in yours. Moreover, one must remember that people moved a lot in the last century, especially in Russia and the Soviet Union, so if your historical information point to, say, Smorgon in the Vilna province, and the live contacts tell you that they come from Moscow, it does not mean that they are not related to you. Just file away the information and move on to the next lead, guided by the intuition and assumptions. Which brings us to the next topic.

There is no substitute for knowledge

There is no substitute for knowledge. I said it five years ago and twice today. We cannot know it all, even if we have talents on loan from G-d, as Rush Limbaugh quips. But there are certain historical facts that are very important for genealogist to know because they allow us to make intelligent assumptions. A good example is the War of 1812, not the war in which the British burned Washington, DC in 1812. We are talking about the War of 1812 in which the French invaded Russia and burned another capital - - Moscow. And on the way to and from Moscow they went through most of the Pale of Settlement, including the very real town of Smorgon, from which one fictitious Nosel Goldman departed 90 years later.

Fig. 1. Retreating Napoleon's Army burns Moscow.

From the 19th century painting

Why is the 1812 War important to us? - Because the Russian Fiscal Census, known as Revision Lists to genealogists,

was conducted before and after the war, that is in 1811, and 1818, and it does exist for many towns in Belarus, Lithuania, and Ukraine.

The War of 1812 was one of many cataclysmic events that affected Russian Jews. Even a short version of the time line shows there were many events that caused great

migration of the Russian Jews, including, perhaps, your very own ancestral families.

| 1765-1795 | Partitions of Poland between Russia, Prussia, and Austria. |

| 1795-1915 | Russian Jews are restricted to live inside the Pale of Settlement, with some exceptions |

| 1820s-1840s | Jews from Western area settle in agricultural colonies of “Novorossiya |

| 1840s | Siberian gold rush. A relatively small number of Jews goes East. They become involved in trade. |

| 1863 | Many Jews are exiled to Siberia as a punishment for their participation in the Polish uprising. |

| 1881 | First major wave of pogroms leads to mass emigration from Russia |

| 1914-1915 | During World War I, Jews were expelled from the front areas |

| 1917-1939 | The two revolutions of 1917 abolished the Pale of Settlement. The Jews started migrating in relatively large numbers to big cities including Moscow and Leningrad |

| 1917-1920s | Many Jews, primarily those from Siberia, emigrated to Chinam mainly to Harbin. |

| 1934 | Jewish Autonomous Region was founded in the Khabarovsk region. |

| 1939-1941 | Poland was divided, once again, between the Soviet Union and the Nazi Germany. |

| 1941-1945 | Soviet Jews as well as non-Jewish refugees, settled throughout Siberia, Far East, and Middle Asia. |

| 1945-1950's | Former Soviet Jews, primarily those from the Baltic states, went to DP camps and from there to Palestine, US, and elsewhere in the West. |

| 1945-1946 | Harbin Jews escaped to US, Australia from the advancing Soviets. |

| 1950's | The Soviet Union allowed “former citizens of the Polish Republic” to resettle in Socialist Poland. |

| 1960's | Jewish emigration to Israel is allowed in small numbers from the Baltic republics. |

| 1971-1979 | Mass Jewish emigration to Israel and from ca. 1975 to US. |

| 1991-present | After the demise of the Soviet Union, mass Jewish migration took place both inside the former USSR and throughout the world. |

Knowing history on both global and local levels enriches one’s research and often shortens the path to finding ancestors.

This became evident to me recently while researching vital records, mostly Polish-Jewish, that have been microfilmed by the Mormons. The subject is very interesting and rightly deserves the attention it gets, including at this conference. My contribution to it can be summarized as follows:

How to quickly research Polish (and Russian) microfilmed records

Why quickly? Because the are too many that must be researched, and the life is too short.

Why microfilmed? Because I refer to those records that were filmed by the Mormons and are available to each of

us as entire collections of Jewish vital records for a number of towns in Russia

and Russian Poland.

Those who attended Judith Frazin’s presentation on Monday at this conference or used her books, must have learned a lot. My goal is more modest. I would like to share my experience in navigating these records, quickly recognizing names and selecting appropriate frames for copying and further analysis.

Why is it important to be able to research the original records when there are at least 1.8 million of indexed records from Russian Poland available on the web?

The very existence of these indexes is the reason No. 1. They are 1.8 million pointers to actual records but not the records themselves. One cannot imagine how much more information one can glean from studying actual records, as microfilmed images.

Reason No. 2 is that computerized records are only relatively accurate. Stanley Diamond wrote to me once:

If 95% of our data is accurate, we would be pleased. While 5% error rate seems reasonable, 5% of 1.8 million translates into 90 thousand missing records. That’s almost the entire Jewish population of Vilna before the Holocaust. The point is that we may be indebted to the people who made the JRI indexing project possible, but our work must not stop there, on the web.

So how do we begin the LDS microfilm research? We begin by doing homework. Even if you have all the time in the world, there is only so much that your eyes and lower back can suffer.

(My personal limit right now is seven hours of non-stop scanning records and hitting the print button. After that I start losing concentration.)

I usually come to the LDS library with all the printouts of the computerized indexes, so I know roughly what to expect. If you are not fluent in the languages of the records, the best self help tool is a collection of your ancestral names and towns written in the Russian Polish, Yiddish, German - whatever you can find.

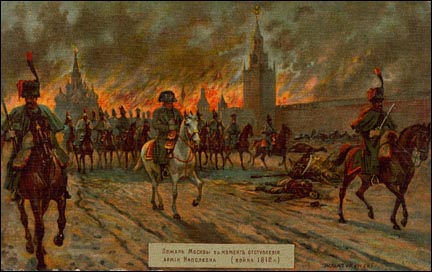

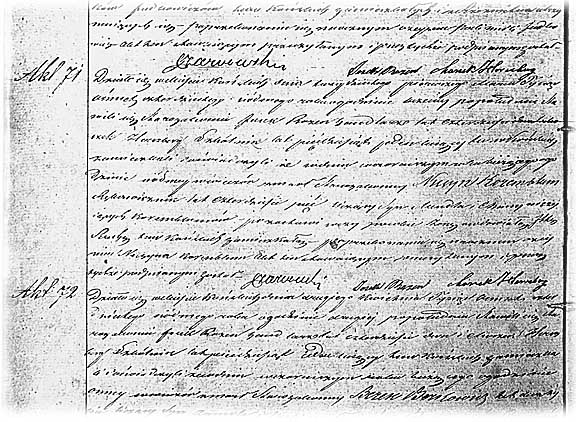

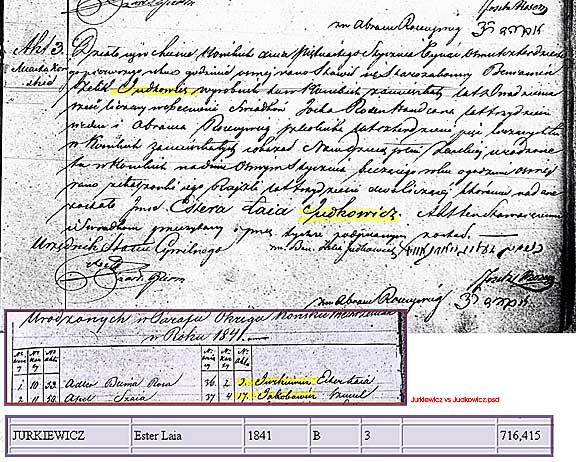

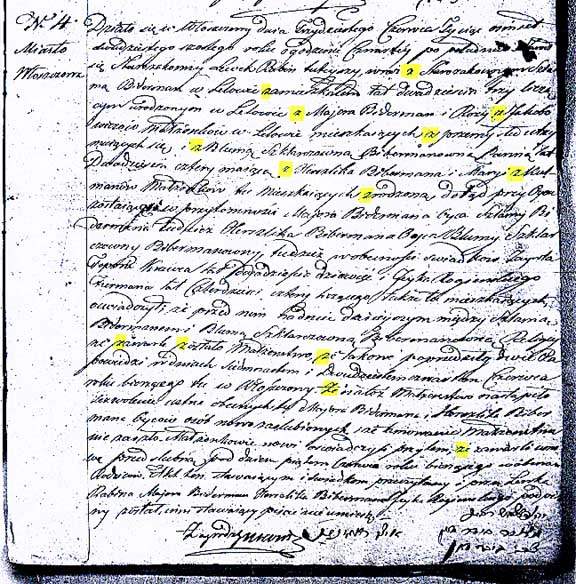

Fig. 2. Examples of hand-written given names copied from 19th records

One such example is shown in Fig. 2. These are names from the Kremenets indexing project, managed by Ron Doctor and Sheree Roth who have done an amazing analysis of the records.

I am often asked by genealogists to write this or that name in Russian and every time I tell them

You do not want my handwriting, you want the name in OLD Russian, and more than one sample because every clerk had his own writing style, especially for capital letters which can throw you off track if you misread them.

So you come to the Mormon library well prepared. You loaded the film. You place a frame on screen and focus the image, your eyes, and your mind.

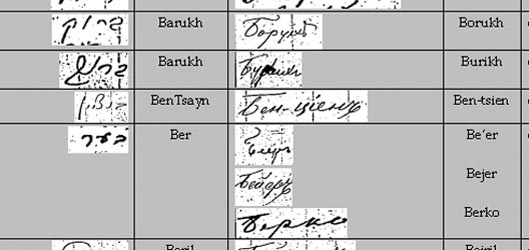

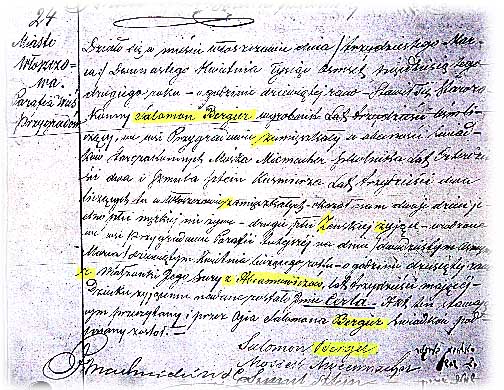

Fig. 3. Page from a Jewish vital records register

... And you feel a little bit deflated. Where do you look for these names? How to make sense of it all?

As we know, vital records from Russian Poland followed several formats. Birth records were compiled in a certain fashion, marriage records differently, and so on. Except that the pre-1826 records differ from post-1826, and except that the records were in Polish till 1867, and then in Russian, and except that every clerk was free to introduce something different, depending on the year, his mood, and the

weather. You do need a full translation in order to get maximum information and to make discoveries. However, that will come later. The main challenge, while at a Mormon library is to quickly find and recognize your family names. You do not need to know Polish or Russian to achieve this goal. Because there are certain recognizable patterns in these records, one can look for names in certain places in a record. It is almost like looking at a map, so one of the tricks I simply call mapping

the records.

Fig.

An index can be found most often in the end of the register, but often enough in the beginning. There are many discrepancies between the records, and the indexes, and between handwritten and computerized indexes too. I always print copies of all index pages, when they are available. The reason is simple. If you ever need to revisit a particular collection, you will not have to order a microfilm and wait a month. I also compare the number of actual records against the number of indexed names. Sometimes blocks of names are

missing from the handwritten index, and you never know whether the computerized index was compiled off a handwritten one, or directly from the records. So the reason to study indexes before looking at actual records, is obviously missing information.

Here are some of the typical errors found in the record:

|

- a record and its index entry exist, but are missing in the computerized index; - a record exists, but is missing in both handwritten and computerized indexes; - a full name is recorded, but the surname is not in the handwritten index; - surnames in the record and the handwritten index are different; - record numbers are different in the register and the handwritten index; |

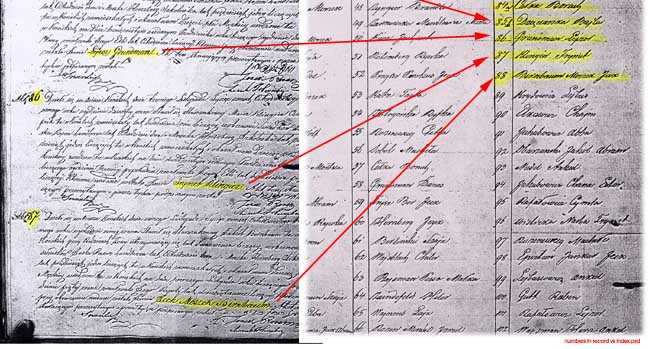

Several examples of such errors are shown bellow:

Fig. 5. Surname Wislicki is missing in the handwritten index and in the computerized index

Fig. 6. Surname Judkowitz in the record entered as Jurkiewicz in the handwritten index and in the computerized index

Fig. 7. Record 87 is for Icyk Moszek Birnbaum; index entry 87 is for Frymet Klyngier

Records themselves often contain conflicting information. Sometimes it’s a simple spelling variation, e.g. Hilerowicz vs. Hillerowicz vs. Chilerowitz; at other times you may encounter two different names for the same person:

Fig.

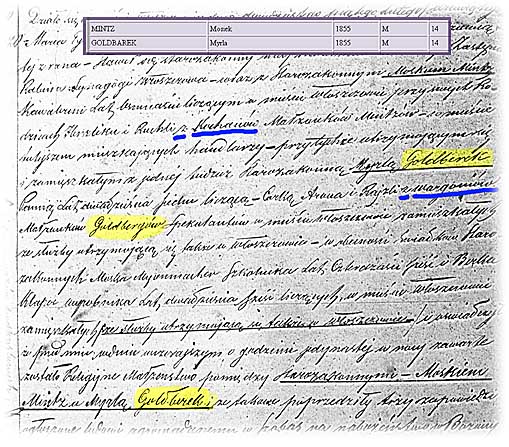

The Help of Zorro

Index or no index, you take a deep breath, put the frame on screen - and you feel like crying for help. It comes to you, as promised, from Zorro.

You never thought that Zorro will would help you read Polish Jewish Vital records from 1843. You would be surprised. No, he was not Jewish,

neither was he a descendent of the Vilna Gaon.

For our purposes, you only need to remember the letter Z, associated with his name. It is a very important letter. In Polish, and to a lesser extent in Ukrainian, Z is a preposition meaning several things, e.g.

Boris z Potomaku means Boris from Potomac, Sandra z

Zimmermanow, or Sandra z domu Zimmermanow means Sandra from the family of

Zimmerman or

Sandra from the house of the Zimmermans; expression z malzonki jego Malki in birth records means

to his wife Malka , e.t.c..

Scanning a Latin script record for the letter Z is easy, so one quickly discovers that it is almost always followed by a name or a

town; or, that it is preceded by one; or, that it’s the first letter of an important word, like

zamieszkaly, i.e. residing, living.

Fig. 9. Letter Z as a pointer to family and town names

|

Polish |

English |

|

... z starozakonnego Szlama Bidermana... |

[Rabbi] came with ... Szlama Biderman |

|

...w Lelowie zamieszkali... |

...residing in Lelow... |

|

..z Majora Bedermana i Ruchli z Jakobowiczow... |

...[born to] Major Bederman and Ruchla ne Jakobowicz |

|

...i z ... Bluma Bibermanowna... |

[Rabbi] also came with ... Bluma Biberman... |

|

...z Herszlika Biebermana i Maryi z Kulmanow... |

...[born to] Herszlik Bieberman and Marya ne Kulman |

Cherchez La Femme

Alexander Dumas who coined the phrase 140 years ago in one of his novels (Les Mohicans de Paris) was not Jewish either. Consider this phrase a mnemonic

device to a very important element of research. It is well known that women in Western society changed their family names upon marriage. Their maiden names were practically never included in the

vital records summary index back in the 19th century, and as a consequence are missing from computerized lists that are based

on these indexes.

The only way to discover these maiden names - and family connections - is to comb the actual records. That’s were the letter Z will help you, although not always because of grammatical errors and alternative ways to describe family relations. Moreover, there is no guarantee the maiden names are listed, but that’s

the nature of research. We do not now the results until after it is completed.

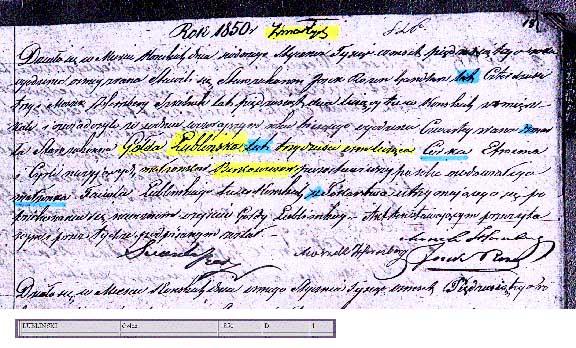

A mother’s maiden name is easy to spot on a birth record, because it is always listed toward the end of the record (see Fig.

10). The record also shows the two clearly different spellings of the family name: Bergier and Berger, and three different ways to write capital letter B.

Fig. 10. Mother's maiden name on a birth record

Death records of married women and widows are of specific interest because they can list, in addition to the married name, the deceased woman’s maiden name, and the maiden name is missing in the computerized index.

Fig. 11. Mother's maiden name on a death

record

Of course, finding a woman’s maiden name may be both a blessing and a curse, if a woman married her cousin with the same last name - which was not a rare occurrence. For us, every such occurrence becomes another brain twister. That’s the challenge and the beauty of research. Studying the records

meticulously will allow us to see new ways to analyze them and learn more information than we have originally thought existed. You just saw how many records contain more names than just the direct participants in an event. This opens new research possibilities with untold benefits.

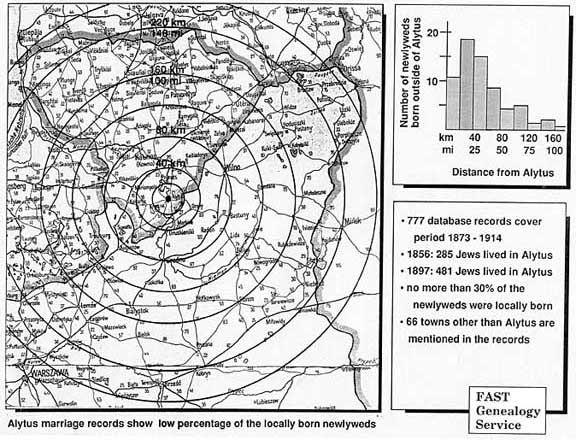

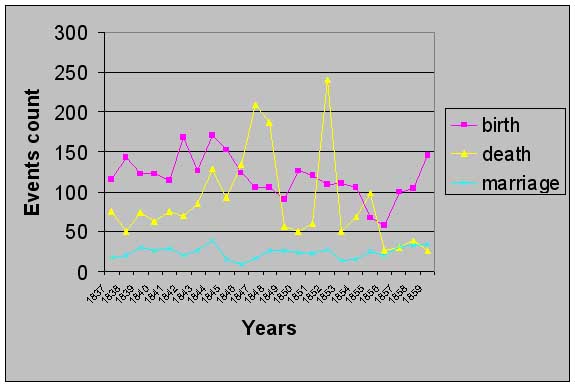

Fig. 12. Jewish marriages in Alytus (also Olyta), Lithuania

When studying a record collection, do not be surprised if a spike in marriages in one particular year

is not followed by the birth rate increase in subsequent years. The newlyweds were still fruitful and multiplied - but not in the same town where they married.

Statistics are important in genealogical research to a certain extent, as a tool that increases our understanding of historical trends, and which allows us to make educated guesses in our study of personal histories.

Fig. 13. Konskie vital records analysis

Researching vital record collection from the small Polish town of Konskie, I saw that it went though two devastating epidemics in 1848 and 1853. This was a tragedy that no statistics can help us comprehend. But it can help us understand the life of our ancestors and motivations behind their actions.

Imagine researching a family line. You came to this year and discovered that the family was pretty much wiped out, except for one son who is your direct ancestor. Then you discover that another teenage son is missing in later records. He is not listed among the dead, yet there is no marriage record of him ten years later. There is a possibility that he died too, and no record was made. But there is another possibility that his parents sent him away to uncle Chaim in Plonsk, or sister Bejla in

Warka. Knowing connections between families and towns may help you - 150 years later - to locate a missing person.

The other version of this puzzle is when we research a collection going back in time, and stop at some Chaim-Yankel in Plonsk in 1850. After that, there is no trace of him or his parents or siblings even though the records exist and go back all the way to 1817. It obviously means that Chaim-Yankel lived somewhere else before 1850. In most cases, his previous residence or a town of birth will be listed. If it is not - we can analyze other marriage records from Plonsk to learn towns from which other newlyweds came.

To summarize, records must be analyzed not only for family connections, but for town connections as well.

And, as I said earlier, this approach works not only for Polish records, which I used as an illustration, but for other locations in Russia for which record collections exist.

The Siberian connection

It is often overlooked that many Jews from the Pale of Settlement migrated to Siberia.

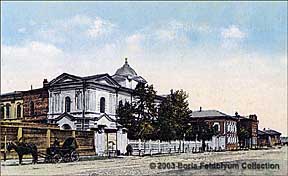

Fig. 14. Synagogue

in

Tomsk

Fig. 15. Synagogue

in Irkutsk

A simple look at the early 1900 photo of the synagogue in Tomsk tells us that the community was sizeable and probably relatively secure (as far as “security” of Jews in Russia goes). The somewhat audacious design of the large stone synagogue is a good indication of

the Jewish community's status in the city.

The wooden synagogue in Irkutsk was modest by contrast, but also very large. Irkutsk had a large Jewish population in the early 1900s, comprised of Jewish political exiles, adventurers, and those who joined them. Analysis of surnames from a 1900 Irkutsk birth register

(Fig. 16) clearly points out to many locations in the Pale of Settlement.

Fig. 16. Surnames in a Jewish birth register from Irkutsk point to the Pale of Settlement

To summarize, there are many strategies that lead to success. I thought of sharing a few ideas with you today. When it comes to missing relatives and missing information, in can be really frustrating, and I do feel you pain. On the other hand, we can benefit from Zorro or Alexander Dumas, and it does not stop with them. There is a truism well known in the intelligence community:

The Absence of the Evidence is not the Evidence of the Absence.

This principle applies not only to search for weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, but to searching our own Chaim-Yankel from Plonsk.

We must always keep our mind open and be creative in research. That’s what makes genealogy great.

A NOTE, five years

later. I beg your forgiveness, dear reader, for the imperfections in

grammar and style. As Victor Borge said: It's your language, I am only using

it. The truth is, I have never had the time to go back and polish the

notes. Alas, the language is not prfect but the ideas are still brilliant.

It hurts to think how smart I once was.

![]()

Good luck in your search.